The State of the Humanities

When an undergraduate contemplates studying the humanities, he or she is bound to hear of their impracticality. Since the success of early careers is often defined by measurable outcomes (particularly one’s postgraduate salary) any study of unquantifiable sensations or ideas may seem useless in the face of industry demands and dehumanizing technologies. The humanities are so fragile, so out of sorts with the world’s increasingly sophisticated challenges, that their proponents appear to be at the whim of forces beyond control and comprehension. If they’re not building machines or trading stocks, how can these stuffy academics expect to carve a meaningful niche in society? How can they legitimize the study of the humanities—that ambiguous range of fields the Stanford Humanities Center describes as “the study of how people process and document the human experience?”

This essay does not attempt to prove that studying the humanities is “worth it”—though the question of “worth” and how it is defined will be a principal consideration. Rather, the goal is three-fold: one, to summarize the extent of the humanities crisis in American higher education (and to specify what is meant by “crisis,”) two, to supply arguments for and against the continued support of humanities programs, and three, to present the rewards and drawbacks of conducting professional humanities scholarship. I acknowledge my bias as a former graduate student and offer no concrete solutions for ensuring the survival of the humanities in the future. I simply recognize the facts and general concerns that inform debates surrounding the state of the humanities today.

First, there is the basic question of how to measure the value of a humanities education—one that may have different answers at multiple stages of an academic career. In American kindergartens and high schools, it is highly unlikely that the core humanities subjects of English, history or foreign language will lose their place within standard curricula. The importance of being able to read, write and think critically—skills integral to success in college and in most white-collar jobs—guarantees the continued instruction of these topics to children, adolescents and teenagers, and is indeed a principal defense of why humanities instruction should continue or even expand in primary and secondary schools. What really concerns humanities advocates, whether they be dedicated academics, casual scholars or university administrators, is the declining enrollment of bachelor’s candidates in undergraduate humanities programs. According to Humanities Indicators, an ongoing research project initiated by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, in 2015 just less than 12 percent of all bachelor’s degrees were awarded in the humanities, and the downward trend has since continued. The exact reason for this decline is hard to pinpoint, but when young people become more independent, assume new responsibilities, and must decide on the lifestyle or career they want to pursue after college, they may also consider the practical implications of their courses of study. The consequence of this reflection is that the humanities—disciplines that do not feed directly into specific professional schools or career tracks—appear to be an unwise choice.

With fewer undergraduates deciding to major in the humanities, departments require fewer teachers, fail to receive adequate funding, and must cut back on the number of tenured or tenure-track faculty. Departments admit fewer graduate students, and of those students even fewer secure desirable teaching positions in higher education. (That being said, Humanities Indicators shows that a little over half of graduating humanities Ph.D.’s will teach in universities, some as short-term adjuncts or postdoctoral fellows, and others as assistant professors.) It is a

sad, but almost comical scenario—because too many eighteen-year-olds are wary of the idea of studying literature for four years, an entire profession is in danger of collapse. But though the job market remains tight for graduate students seeking faculty positions, and though humanities departments of all varieties must weather a storm of trite criticisms from politicians or concerned parents, it is clear that at least some universities have begun to acknowledge and respond to these issues. Some departments market themselves as safe choices for undergraduates fearful of the job market, insisting that becoming a humanities major is not an act of career suicide. The Stanford English Department is a telling example—under the Academics tab on their website, the subfield “Careers After an English Major” lists a number of industries alumni have entered not in spite of their experiences as English majors, but because of them. It has always been common practice for departments to attract majors by promising fulfilling careers after graduation, but now that the overall number of humanities majors continues to drop, these efforts have taken on greater significance.

And the cute testimonies of recent alumni who actually enjoy their jobs are not merely anecdotal—there is statistical evidence that a large proportion of humanities degree holders, in their own perception, do pursue rewarding careers. These data again raise the question of how best to determine the value of a humanities education, but according to even the simplest metrics, there does appear to be some basis for the argument that studying the humanities is worthwhile, from even the most practical standpoints. Consider the median earnings of humanities graduates in their first few years after college. According to Humanities Indicators, in 2015 the median income for humanities graduates was 52,000 dollars per year, which is considerably lower than the median income for engineering graduates (which stood at 82,000 dollars per year) but was

also markedly higher than graduates who did not receive a four-year college degree or who studied the arts and education (48,000 dollars per year and 44,000 dollars per year, respectively). Moreover, according to the same report, in 2015 those college graduates who obtained advanced degrees in any field earned substantially more than those who only held bachelor’s degrees, and across disciplines, earned a salary that was roughly 33% greater than that of their less educated counterparts. These statistics appear to disprove the notion that humanities degree holders earn laughably lower salaries than their peers who become engineers, businessmen, or doctors. They earn less, but not so much less as to render the humanities a totally unremunerative course of study, and if these individuals go on to pursue advanced degrees, their earnings potential definitively rises.

There are three more noteworthy findings from this report. One, work experience tends to shorten the gap between graduates who receive a “practical” degree versus those who receive a humanities degree. Over the course of several decades, the correlation between an individual’s earnings and variety of bachelor’s degree weakens, and some humanities degree holders will earn as much as or more than peers who studied quantitative disciplines. Two, humanities degree holders claim to be financially satisfied on a level similar to graduates from other fields and also expressed comparatively high job satisfaction. Around 40% of humanities graduates claim “[they] have enough money to do everything [they] want to do”—an opinion shared by an equal proportion of graduates from education, business or social science programs—and appreciate the “opportunities for advancement and benefits” their job affords. They also enjoy the location of their workplace. (Compared to other graduates, however, humanities alumni tend to feel they are underpaid.) Finally, humanities students do not funnel themselves into unemployment or totally

menial occupations. One third of those who graduated with only a bachelor’s degree found work in the service sector, typically in sales or marketing, while one third of graduates holding advanced degrees went on to work in education, with significant minorities also working in law or management. In short, this entire study indicates that studying the humanities as an undergraduate—or even as a graduate student—does not preclude someone from finding gainful employment, and becoming a humanities major does not always result in a life of indigence.

But what about the value of humanities scholarship in and of itself? Can learning be its own reward? And though humanities programs have long been a central feature of university education, should they continue to be? Outside of the supposedly bleak job prospects of humanities students, the nature of humanities education within the university system has also attracted criticism from a variety of sources, whether they be conservative parents who don’t want liberal professors to brainwash their kids, or politicians who insist that a humanities degree doesn’t encourage the pursuit of work valuable for society. Unlike other arguments, these criticisms are more difficult to contest, as they demand that a humanities curriculum defend itself on the basis of content, not a desired outcome (that is, a job, which I have shown to be an achievable prize).

Most popular counterarguments hold true to several trains of thought. Some scholars contend that the humanities are necessary for equipping individuals with a sense of right and wrong. Others argue that the humanities have long been the foundation for a liberal arts education, and without fostering an effective balance of academic topics, the university would underserve its students and undermine its mission. Others still argue that the humanities are worthy of study simply because they are beautiful and useful for contextualizing one’s personal

experiences, specifically insofar as they allow the individual to connect his singular interpretation of the world to that of the famous thinkers who preceded him. (“Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto,” wrote the playwright Terence presciently.) But finally, some practitioners of the humanities opine that all of these defenses are tired and uncompelling, and to preserve the humanities we must admit that they lack intrinsic value.

In “There Is No Case for the Humanities,” published in the political journal American Affairs in 2017, the Oxford classicist Justin Stover argues bluntly that none of the traditional arguments for the humanities hold water, and they never have. He makes the claim that the value of the humanities has been systemically endowed by the university, which would not exist as an institution were it not for research and scholarship in the arts. The humanities, which had once been central to the university experience—and indispensable for schools that wanted to achieve status as establishments of higher learning—have now become a supplementary feature of the university’s intellectual community. The reason the humanities have persisted for centuries, he states, is that they indicate a certain class, united by taste, that begets its own membership through education. The liberal professor that extolls the virtues of Thoreau is not trying to pour his own brand of propaganda into unwitting students’ ears. Rather, the indoctrination is of a different, and more innocent sort—the professor only wants his students to enjoy the humanities with a fervor similar to his own.

Unlike other disciplines, it is certainly clear that the humanities attract students largely because of the passion and interest they excite, not because of the immediate, material rewards they provide. In this sense, therefore, Stover is right to classify them as an expression of collective interest, or courtoisie, that denotes an enlightened in-group and quietly marks off an unenlightened out-group. But his claim that the humanities are inherently useless is harder to accept, and far too sweeping to evade basic refutation. The written word is the essential building block of several industries, including journalism and publishing, that not only form a vital, albeit small portion of America’s economy, but also facilitate the running of a transparent, effective democracy. The ability to teach—perhaps not a defining aspect of “pure” humanities research, but a concomitant skill nonetheless—is crucial for encouraging young people to make their own decisions and draw conclusions about an uncertain and dissimulative world. And even Stover is quick to admit that were it not for the obscure and ostensibly purposeless exploits of humanities scholars—some of whom might relish topics as strange as the depiction of trees in Romantic paintings—the university as it is structured today would cease to exist. To paraphrase Stanford professor Mark Greif, the university allows individuals who embrace the arcane and the aberrant to explore their interests in a way that greater society does not.

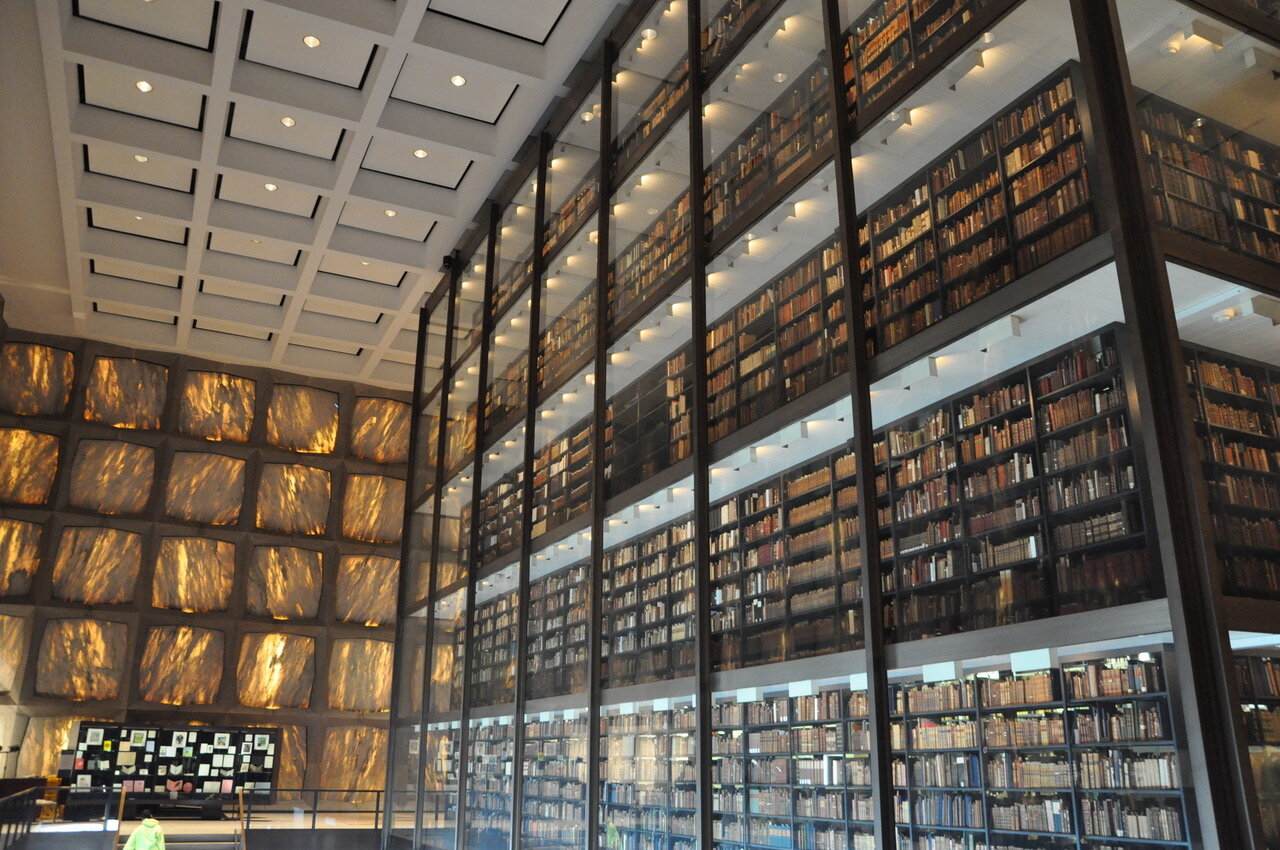

But even in the university, where the tree-loving scholar takes refuge, structural violence threatens to force her into the light. The ivory tower is not untouchable, and though nobody is evicting students from libraries, academia no longer provides the same security, financial or intellectual, that it once did for graduate students and professors. In response to Stover’s article, Professor James McWilliams of Texas State University provides a more hopeless view of the situation, asserting that humanities study does not confer the same intellectual status in the United States as it does in the United Kingdom, where the esteem of universities like Oxford and Cambridge deflects any critique of their importance as community-serving institutions. In the United States, college administrators are willing to gut humanities programs for financial gain. The passions of a few comparative literature undergraduates do not serve as an adequate defense against the pressures of the market, and though these students and their graduate doppelgängers may wish with all their heart to avoid the encroachment of capitalism, they must recognize, sooner rather than later, that resistance is futile.

So how can humanities departments confront the pressures of that amorphous and inscrutable monster known as “the real world?” There are no easy answers, but the prevailing recommendation seems to be that universities must revamp their approaches to graduate education and steer interest towards untapped audiences. If students can no longer become professors as quickly or easily, it is critical to adjust how they gauge their success. According to Earl Lewis, the last president of the Mellon Foundation, if the Ph.D. does not lead to a career in academia, it must also be valuable as a life experience that informs personal development and career choices in unexpected and assuring ways. Moreover, it is probable that the humanities may thrive outside of higher education, and with the surging popularity of alternative mediums, like podcasts, millions of people may themselves become literature buffs without even breaching the university’s ivy-laden walls. I cannot imagine a future without humanities scholarship—the work encourages and validates cultural output, and is itself a form of creative expression. However, should our struggling field want to thrive, it will first need to wake up.